RATING

Director(s): RaMell Ross

Country: United States

Author: RaMell Ross, Joslyn Barnes, Colson Whitehead

Actor(s): Ethan Herisse, Brandon Wilson, Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor

Written by Tom Augustine.

The bold and shimmeringly gorgeous Nickel Boys is adapted from the Colson Whitehead novel. Whitehead was in Aotearoa just last year for the New Zealand Writers’ Festival — and beyond that, the subject matter that Nickel Boys tackles, with its investigation of terrible abuses at a reformatory academy for wayward youths, is of particular interest and concern for New Zealand audiences at present, with the horrifying reopening of military style camps introduced this past year amidst the uncovering of historical abuses at camps past. So why is it that RaMell Ross’ Nickel Boys, comfortably the very best of the assembly of films nominated for the Best Picture Oscar this year, is suffering the shocking injustice of being denied a cinema release? Much in the same way that great films used to be shuffled off to DVD-only releases in the old days, the straight-to-streaming dump has become a go-to for distributors who, for whatever reason, don’t have the confidence that these films will find an audience, and precedent or artfulness of said offerings be damned. In recent times, remarkably great films like Clint Eastwood’s Juror #2, Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World and Justin Kurzel’s The Order have faced this ignominious fate. In the US, even the surefire hit Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy somehow bypassed cinemas to be dumped on streaming service Peacock. Nickel Boys is not even the first recent Best Picture nominee to have this happen in Aotearoa — 2024 nominee American Fiction went the same way, despite also having the pedigree of a locally popular author in Percival Everett, whose James was in the hands of every literary type I know in the second half of 2024 (it’s worth pointing out that, in both American Fiction and Nickel Boys’ case, Amazon was the distributor. Make of that what you will).

So why was Nickel Boys bypassed? I want to believe we as a country have come further than the days of video stores, when my old manager wouldn’t ever buy more than a single copy of black-led films because ‘New Zealanders don’t want to watch films about black people’, a lesson he’d learned the hard way in trying to move black-led offerings that weren’t actions starring Denzel Washington. And yet, for every Moonlight and Get Out and Black Panther, films of such magnitude that it was virtually impossible to ignore them, there are smaller black-led films like The Inspection, Luce, Blindspotting, Fruitvale Station, Time, and so on, which pass with nary a glance in this country. How many people sat down to watch Barry Jenkins’ The Underground Railroad, despite Moonlight beating the odds a few years prior? Even Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, one of the finest films of the decade, didn’t warrant a cinema run. It’s particularly depressing in the case of Nickel Boys, a superlative film from RaMell Ross, which represents the emergence of a fearless auteur remolding the ‘black story’ in a way that effortlessly straddles the demands of traditional, emotional narrative with something more artistic, experimental and poetic. All I can say is that it’s a film that demands your attention, a big screen and a darkened room, if you can get it. In a just world it would be the Best Picture winner this year.

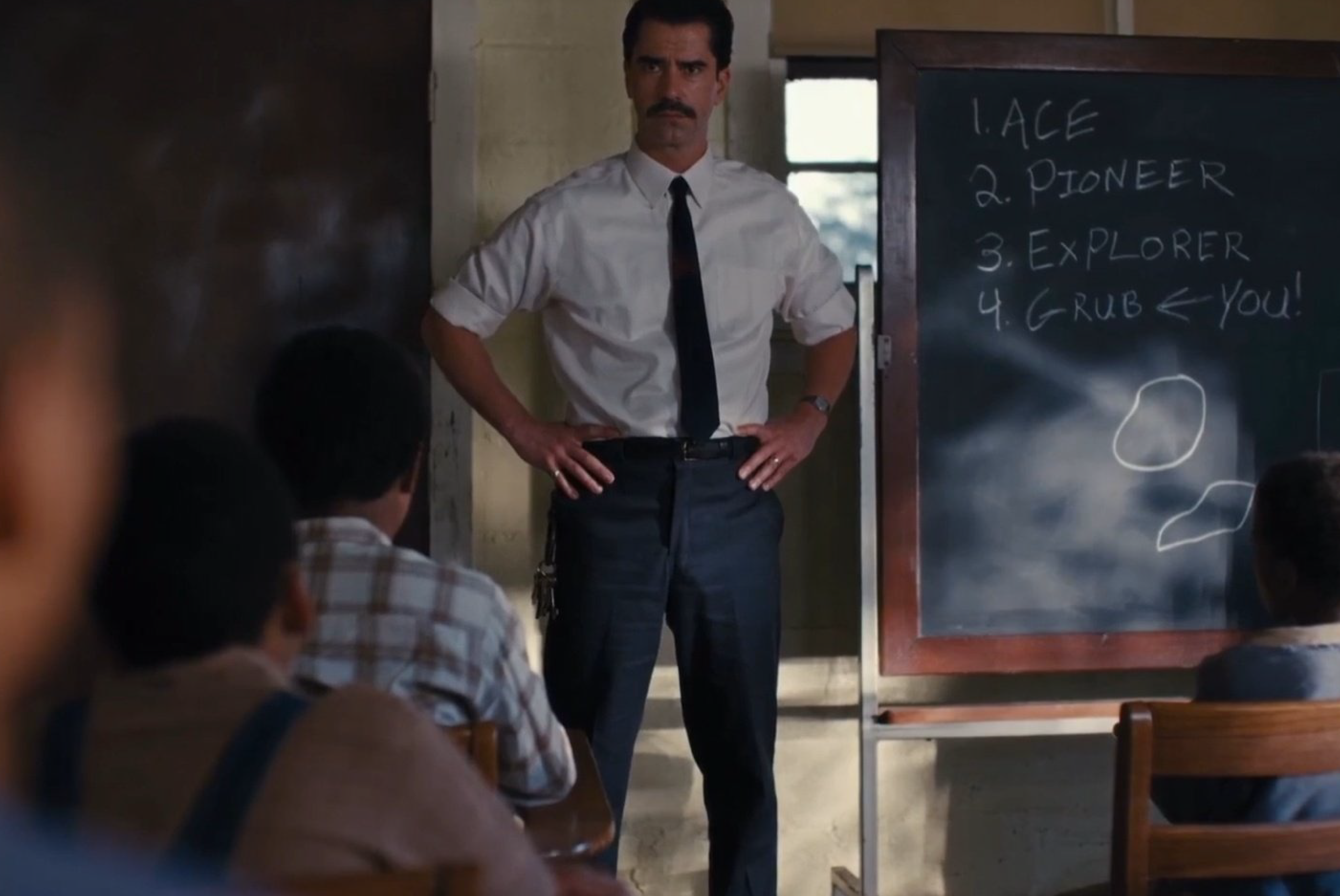

Perhaps it’s because we think we know this story that Nickel Boys seems preordained to inspire reluctance in prospective viewers. It’s a fact that the film itself recognises and tackles in a truly original way. It’s the story of two black boys in the 1960s, during the days of Martin Luther King Jr, who by unfortunate turns of circumstance are sent to the reformatory Nickel Academy, a brutal youth camp where the boys are alternatively used as slave labour and outlets for the white overseers’ frustrations and desires. Nickel Academy is, of course, based on a real place — the Dozier School For Boys in Florida, which over the course of 111 years hid a legacy of murder, rape, torture, beatings and any other number of abuses against vulnerable children. The school was closed after scores of unmarked graves were uncovered across the grounds. That’s a story we know, we’ve heard before, the contours of which we’re largely familiar with. In New Zealand, the scale of abuse was similarly widespread. Nickel Boys, then, takes the contours of this story and keeps them as such — merely contours. The schools definitions are only passingly defined — what the day to day work of the boys is, what kinds of abuses they suffer, the fates of boys who appear briefly on screen, then are never seen again. Superintendent Spencer (Midnight Mass’ Hamish Linklater), who justifies abuse and murder by claiming it’s all part of reformatory practice, is, simply, a brute and a racist. We never see him as more than that — that’s all he is, and all he deserves to be. Into the spaces left by such thin sketching Ross instead floods us with images — symbolic, archival, profoundly suggestive — to stir up feelings and spirits in equal measure. In this sense, Ross’ previous film Hale County This Morning, This Evening is instructional. It’s remarkable to see how Ross has taken the traditional, handsomely prestigious narrative of Nickel Boys and applied it to his own surreal, stream of consciousness approach, elevating both the material and his own directorial voice in the process.

The only Best Picture nominee this year to suffer the ignominious fate of a streaming-only release in New Zealand, RaMell Ross’ remarkable, harrowing Nickel Boys also happens to be the very finest of said lineup. Making use of a brazen stylistic gambit that never feels like a gimmick, it’s a bold, haunting tone poem that at times feels like it’s inventing a new way of watching cinema right before our eyes.

Most of the oxygen spilled on Nickel Boys will go toward its most brazen stylistic gambit, which is the decision to play out the film almost entirely in point-of-view shots of its two leads, Elwood (Ethan Herisse) and Turner (Brandon Wilson). Cinematographer Jomo Fray, in the most accomplished camerawork of the year, stands in for the two actors, capturing the experience of this world through their eyes. It is not the first time that a film has been told entirely via point of view camerawork – Hardcore Henry, anyone? — but rarely has it been used to such potent and poetic means. The line at which a stylistic choice trips over into storytelling gimmick is very thin, but we know it immediately when we see it. Iñárritu’s godawful one-shot takes in The Revenant and, to a lesser extent, Birdman, are fine examples, but the same approach in Cuáron’s Children of Men works gangbusters. 1917, Sam Mendes one-shot film that earned copious praise and derision from different critical and awards wings, has grown better in the years since its release — the experiential intensity of its action sequences pack a harrowing, exhausting punch. From the opening frames of Nickel Boys, though, we know Ross’ approach is no attention-grabbing stunt. Instead, it is carefully considered, playing into those contours, forcing the audience to remove the distance at which we hold a story such as this. It’s remarkable just how easily one finds themselves naturally slipping into the perspective of the boys while watching. Even though their faces and emotions are so often withheld, we fill that space with our own emotions naturally, because we know this story through the cinematic depiction of such suffering across so much of cinema history (The Defiant Ones, a Sidney Poitier-starring film about a black and white convict chained together and on the run, repeatedly appears in the film, nodding at this understanding as the film’s action plays out). In turn, the viewer is both implicated and invited to step into the shoes of another, quite literally.

It’s Ross’ first narrative feature, which is astonishing. Even more astonishing is that he’s working from a source novel of enormous stature in itself, and yet Ross hasn’t just transposed the work onto the screen, instead remixing and reshaping what has been written into the cinematic form, the apotheosis of page-to-screen adaptation. Comparisons abound — its colour palette and framing often recall Jenkins’ films, but also the work of Black Civil Rights photographer Gordon Parks and filmmaker Garrett Bradley. I was most consistently reminded of Beyoncé’s 2010s masterpiece Lemonade, in the way exquisite montages of semiotic imagery were used to fuse personal pain with generations of cultural suffering and resilience. Nickel Boys feels revelatory for this reason — Ross synthesises decades of visual work from a range of significant black artists, and yet the end result feels utterly new. That the film is nevertheless a profound, powerful emotional experience is yet another unexpected turn. The two boys, Elwood and Turner, represent two sides of the black experience, two sides of the same coin (a penny, another recurring image in the film). Elwood, well-educated and inspired by the teachings of King, believes in the long arm of justice and in the possibility of change. Turner, meanwhile, has had optimism long since crushed out of him, a cynic who is trying to graft a selfish worldview on himself. At the beginning of the film (having not read the source material), I worried that we were in for a Fight Club style twist — that the two would morph into a singular persona. In a sense, that is the case in Nickel Boys, but the scripting is so graceful and Ross’ direction so virtuosic that such a narrative feint is given new, tragic energy by the film’s flooring final third. Both boys come to represent the others’ worldview, each identity subsumed into the other, forming a whole that is genuinely haunting in its implications.

I hesitate to suggest that Nickel Boys is revolutionary. Will it remain in the memory of audiences after Oscar season has come and gone? Will it calcify into the dreaded category of ‘Important Film’ which is so often anathema to rewatchability? Other films that we have lauded as such have diminished into nothingness in the years since. Is anyone still talking about Nomadland, or Everything Everywhere All At Once, or Roma or The Shape of Water, films that were all the rage upon release and yet now seem destined to be passed over in Netflix queues forever more? I think time will be kind to Nickel Boys, as its nominations feel both cursory and kind of miraculous, so strange, gentle and avant-garde is the execution of the storytelling (in spite of the harshness of its subject matter). Its stylistic swing is likely to be alienating to some viewers, and yet, there are so many ways that the film could have been rendered in far more rote and uninspiring terms. There are so many details, so many grace notes and intricacies littered throughout Nickel Boys — animals like alligators and donkeys recur with the weight of anvils; archival footage and home movies are cunningly tampered with; scenes are recut, reshown and recontextualised to layer in meaning and understanding. Ross employs all sorts of photographic measures, from timelapse to simple editing magic tricks, all in service of a grander idea. Scenes of Elwood in the future are shot above and behind the character’s head, floating ghostlike in observance. We most commonly think of cinema as the space of either dream or memory. In Nickel Boys, we see both, collapsing into each other constantly, inviting us to see the world differently, from another perspective to our own.

Nickel Boys is now on Prime Video